I was recently asked by a startup I’m consulting (BigPanda) to give my opinion about the structure and flow of data science projects, which made me think about what makes them unique. Both managers and the different teams in a startup might find the differences between a data science project and a software development one unintuitive and confusing. If not stated and accounted for explicitly, these fundamental differences might cause misunderstanding and clashes between the data scientist and her peers.

Respectively, researchers coming from academia (or highly research-oriented industry research groups) might have their own challenges when arriving at a startup or a smaller company. They might find it challenging to incorporate new types of inputs, such as product and business needs, tighter infrastructure and compute constraints and costumer feedback, into their research and development process.

The aim of this post, then, is to present the characteristic project flow that I have identified in the working process of both my colleagues and myself in recent years. Hopefully, this can help both data scientists and the people working with them to structure data science projects in a way that reflects their uniqueness.

The flow was built with small startups in mind, where a small team of data scientists (usually one to four) run short and mid-sized projects led by a single person at a time. Bigger teams or those in machine-learning-first, deep-tech startups might still find this a useful structure, but processes there are longer and structured differently in many cases.

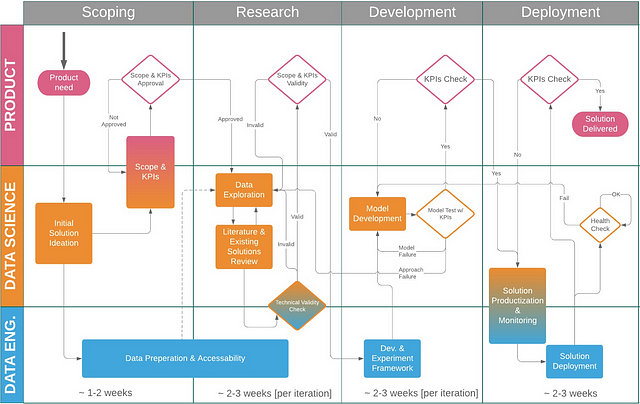

Figure 1: Data Science Project Flow for Startups

I have divided the process into three aspects that run in parallel: product, data science and data engineering. In many cases (including most of the places I worked for), there might not be a data engineer to perform these duties. In this case the data scientist is usually in charge of working with developers to help with these aspects. Alternatively, the data scientist might do these preparations, if they happen to be the rarest of all of God’s beasts: the Full Stack Data Scientist! ✨🦄✨. You can thus replace data engineer with data scientist whenever it is mentioned, depending on your environment.

On the time axis, I broke the process down into four distinct phases:

- Scoping

- Research

- (Model) Development

- Deployment

I’ll try and walk you through each of these, in order.

1. The Scoping Phase

Defining the scope of a data science project is crucial more than in any other type of project.

1.1. Product need

A project should always start with a product need (even if the original idea was technical or theoretical), a need validated to some degree by product/business/customer success people. The product person should have an idea of how this feature should (roughly) end up looking, and that either existing or new customers will be willing to pay for it (or that it will prevent churn / drive subscriptions / drive sales of other products / etc.).

A product need is not a full project definition, but should rather be stated as a problem or challenge; e.g. “our customers need a way to understand how they spend their budgets” or “we do not manage to get our older users to keep taking their medicine; this increases churn” or “customers will pay more for a product that can also predict rush hours at the airports they run”.

1.2. Initial solution ideation

This is where the data scientist, together with the product person in charge, the data engineer and any other stakeholder, comes up with different rough sketches for possible solutions. This means both the general approach (e.g. unsupervised clustering vs boosted-tree-based classification vs probabilistic inference) and the data to be used (e.g. this specific table from our database, or some specific user behavior that we do not yet monitor or save, or an external data source).

This usually also involves some level of data exploration. You can’t go real deep here, but any promising “low-hanging fruits” can help guide ideation.

The data scientist should lead this process and is usually in charge of providing most of the solution ideas, but I would urge you to use all those taking part in the process for solution ideation; I have had the good fortune to get the best solution ideas for a project handed to me by a back-end developer, the CTO or the product person in charge. Don’t assume that different, and less theory-oriented backgrounds, invalidate people from taking part in this phase; the additional minds and viewpoints are always valuable.

1.3. Data preparation and accessibility

The team should now have a good idea of the data that would hopefully be used to explore possible solutions (or at least the first such data set or source). Thus, the process of providing data access and preparing it for exploration and use should already start, in parallel with the next phases.

This can sometime entail dumping large data sets from production databases into their staging/exploration counterparts, or to colder storage (for example, object storage) if its time availability is not critical in the research phase. Conversely, it can mean pulling large data dumps from very cold storage back into table or document form to enable fast querying and complex computations. Whatever the case, this phase is required for the research phase to start and frequently ends up taking more time than expected, and so that’s the right time to initiate it.

1.4. Scope & KPIs

This phase is about deciding together on the scope and the KPIs of the project.

KPIs should be defined first in product terms, but in much more detail than before; e.g. with respect to the three aforementioned product needs, they might become “customers could now use a dashboard with CTR stats and projection per category”, or “missed medicine days by users over 65 will be reduced by at least 10% over the next two quarters”, or “customers will receive weekly predictions of rush hours in their airports with granularity of at least an hour, and approximation of at least ±50%”.

These KPIS should be then translated to measurable model metrics. With luck, these will be very hard metrics, such as “predicting the expected CTR of an ad with approximation of at least X% in at least Y% of the cases, for any ad that runs for at least a week, and for any client with more than two months of historic data”. In some cases, however, softer metrics will have to be used, such as “time required for topic exploration using the generated expanded queries will be shortened, and/or result quality will improve, when compared to the original queries”. This is especially true when the model is meant to assist some complex human function.

Technically even these metrics can be defined very strictly (and in academic research, they usually are), but depending on resources and time constraints we might settle with approximating them using human feedback. In this case each feedback iteration might take longer, and so we will usually try to find additional hard metrics to guide us through most of the upcoming research iterations, with the costlier feedback being elicited only once every few iterations, or on significant changes.

Finally, scope is especially important here because research projects have a tendency to drag on, and to naturally expand in size and scope as new possibilities arise while researching or when an examined approach answers the demands only partially.

Scope limitation 1: I find it more productive to limit scope explicitly; for example, if you’ve decided that a Multi-Armed Bandit based model is the most promising approach to start with, you might define the project scope to a single two/three weeks iteration of model development, deploying the model regardless of its accuracy (as long as it’s over 60%, for example). Then, if improvement in accuracy is valuable (in some cases it might turn out to be less so), developing a second model might be thought of as a separate project.

Scope limitation 2: Another variation on scope limitation is using increasing degrees of complexity; for example, the first project might aim to deploy a model that only needs to provide a rather large set of candidates of ad wording and color variations for your own customer success people to work with; the second might attempt to build a model that gives a smaller set of suggestions that the customer can see herself; and a final project might try for a model that highlights a single option, ranking below it a couple more, and adding CTR projections and demographic reach for each variation.

This is already a huge departure from software engineering, where usually components are iterated over for increased scale rather than complexity.

Nevertheless, the metric-to-product-value function might be a step function, meaning that any model performing under some X value has no use for the customer; in these cases, we will prefer iterating until that threshold is suppressed. However, while this X might be very high in some cases, I believe that both product/business people and data scientists tend to overestimate the height of this step; it’s very easy to state that anything under 95% accuracy (for example) provides no value and can’t be sold. In many cases, however, careful examination and challenging of product assumptions can lead to very valuable products that might not be as demanding technically (at least for the first iteration of the product).

1.5. Scope & KPIs approval

Finally, the product person in charge needs to approve the scope and KPIs defined. It is the data scientist’s job to make sure everybody understand the implications of the scope — what was included and what was prioritized — and the relation between the product KPIs and the harder metrics that will guide her during model development, including the extent to which the letter approximate the former. Stating this explicitly can prevent cases where the consumers of the models being developed — product and business people — understand only during or after model development that the wrong metric was optimized.

General remarks on scoping

In many places this phase is skipped, with the data scientist eager to start digging at the data and explore cool papers about possible solutions; in my experience, this is almost always for the worst. Skipping this phase can result in long weeks or months spent in developing cool models that end up not answering a real need, or failing in a very specific KPI that could have been explicitly defined with some premeditation.

2. The Research Phase

2.1. Data exploration

This is where the fun starts! The main advantage of having this phase commence after scoping is that our exploration can now be guided by the actual hard KPIs and model metrics we have decided on.

As always, there is a balance to be struck here between exploration and exploitation; even when having clear KPIs in mind, it is valuable to explore some seemingly unrelated avenues to a certain degree.

By now the initial set of required data should have been made available by data engineering. However, some deficiencies in the explored data will often be discovered during this phase, and additional data sources might be added to the working set. The data engineer should be prepared for this.

Finally, although separated here from the literature and solution review phase, they are usually either done in parallel or alternated between.

2.2. Literature & solutions review

Both academic literature and existing code and tools are reviewed in this phase. Balance is again important; both between exploration and exploitation, and between diving into the intricacies of the material and extracting takeaways and possible uses quickly.

In the case of academic literature, the choice of how deep to go into aspects like formal proofs and preceding literature depends heavily on both the time constraints and the context of the project: Are we building a strong basis for a core capability of the company or devising a solution to a one-off problem? Do we plan to publish our work on the subject in an academic paper? Are you planing to become the team’s expert on the topic?

For example, take the case where a data scientist embarking on a project to help the sales department better predict lead generation yield or churn feels she has only a shallow understanding of stochastic process theory, on which many common solutions to these problems are built. The appropriate response to this feeling can be very different; if she works for an algo-trading company she should definitely be diving into said theory, probably even taking an online course on the topic, as it is very relevant to her work; if, on the other hand, she works for a medical imaging company focused on automatic tumor detection in liver x-ray scans, I’d say she should find an applicable solution quickly and move on.

In the case of code and implementations, the depth of understanding to aim for depends on technical aspects, some of which might be discovered only later in the process, but many of which can also be predicted ahead of time.

For example, if the production environment only supports deploying Java and Scala code for backend uses and the solution is thus expected to be provided in a JVM language, the data scientist will have to go deeper into Python-based implementations she finds even during this research phase, as going forward with them into the model development phase entails translating them to a JVM language.

Finally, while reviewing literature, keep in mind that not only the chosen research direction (or couple of directions) should to be presented to the rest of the team. Rather, a brief review of the field and all examined solutions should accompany the choice made, explaining the upsides and downsides of each direction and the justifications for that choice.

2.3. Technical validity check

With a suggestion for a possible solution, the data engineer and any involved developers need to estimate, with the help of the data scientist, the form and complexity of this solution in production. Both the product needs and the structure and characteristics of the suggested solution should help determine the adequate data storage, processing (stream vs batch), ability to scale (horizontally and vertically) and a rough estimate of cost.

This is an important check to perform at this stage because some data and software engineering can begin in parallel to model development. Additionally, a suggested solution might turn out to be inadequate or too costly in engineering terms, in which case this should be identified and dealt with as soon as possible. When technical issues are considered before model development starts, the knowledge gained during the research phase can then be used to suggest an alternate solution that might better fit technical constraints. This is another reason why the research phase must also result in some overview of the solution landscape, and not just in a single solution direction.

2.4. Scope & KPIs validation

Again, the product manager needs to approve that the suggested solution, now stated in more technical terms, meets the scope and KPIs defined. Possible technical criteria that usually have easily detectable product implications are response time (and its relation to computation time), the freshness of data and sometimes cached mid-calculations (which are related to querying and batch computation frequency), difficulty and cost (including data cost) of domain adaptation for domain-specific models (domains are most often clients, but can be industries, languages, countries and so on) and solution composability (e.g. do data and model structures allow to easily break a country-wise model down to a per-region model, or to compose several such models into a per-continent model), though many more exist.

3. The Development Phase

3.1. Model development & experiments framework setup

The amount and complexity of setup required for model development to begin depends heavily on the infrastructure and amount of technical support available to the data scientist. In smaller places, and in places not yet used to supporting data science research projects, setup might sum up to the data scientist opening a new code repository and firing up a local Jupyter Notebook server, or requesting a stronger cloud machine to run computations on.

In other cases it might entail writing custom code for more complex functionalities such as data and model versioning or experiment tracking and management. When this functionality is instead provided by some external product or service (and more and more of these are popping up these days), some setup in the form of linking data sources, allocating resources and setting up custom packages might follow.

3.2. Model development

With the required infrastructure in place, actual model development can begin in earnest. The extent of what is considered the model to be developed here varies by company, and depends on the relation, and the divide, between the model to be delivered by the data scientist and the service or feature to be deployed in production. The various type of approaches to this divide can perhaps be captured somewhat by considering a spectrum.

On one end of spectrum lies the case where everything is the model: from data aggregation and preprocessing, through model training (possibly periodically), model deployment, serving (possibly with scaling) and continuous monitoring. On the other end lies the case where just the choice of model type and hyperparameters, and commonly also advanced data preprocessing and feature generation, is thought of as the model.

A company’s location on the spectrum depends on numerous factors: the data scientists’ preferable research language; relevant libraries and open source availability; supported production languages in the company; the existence of a data engineer and devs dedicated solely to data science related code; and the technical capabilities and work methodology of the data scientists.

In case of a very full-stack-y data scientist, combined with enough support from a dedicated data engineer and devs — or, alternatively, with enough existing infrastructure dedicated to the operation and automation of data lake-ing and aggregation, model serving, scaling and monitoring (and possibly also versioning) — the wider definition for a model can be taken, and an end-to-end solution can be used throughout most of the iterations on model development.

This usually means building the complete pipeline first, from data sources all the way to scaleable served models, with simple placeholders for data preprocessing, feature generation and the model itself. Iterations are then made on the data-science-y parts, while keeping limiting the scope to what is available and deployable on the existing infrastructure.

This end-to-end approach can take more time to setup, and each iteration on model types and parameters make take longer to test, but it saves time later paid for in the productization phase.

I personally love it, but it’s complex to implement and maintain, and its not always appropriate. In that case, some parts of the start and the end of the pipeline are left to the productization phase.

3.3. Model test

While developing the model, different versions of it (and the data processing pipeline accompanying it) should be continuously tested against the predetermined hard metric(s). This gives a rough estimate of progress and also allows the data scientist to decide when the model seems to be working well enough to warrant the overall KPI check. Do note that this can be misleading, as getting from 50% to 70% accuracy, for example, is in many cases much easier than getting from 70% to 90% accuracy.

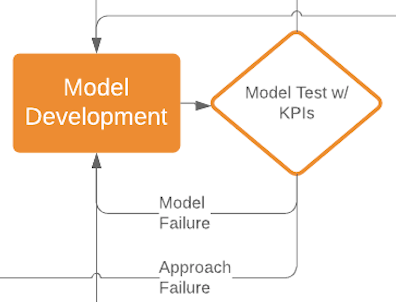

Figure 2: Model failure entails iteration, but an approach failure might send you back to research

When tests show that a model is off the mark, we usually investigate it and its output to guide improvements. Sometimes, however, the gap in performance is very large, with different variations of the chosen research directions all falling short — an approach failure. This might warrant a change in the research direction, sending the project back into the research phase. This is the aspect of data science projects that is hardest to accept: the very real possibility of backtracking.

Another possible result of approach failure is a change to the goal. With luck, it can be minor product-wise but restate the goal technically in a simpler way.

For example, instead of trying to generate a one-sentence summary of an article, choose the sentence in the article that best summarizes it.

The final possible result is of course project cancellation; if the data scientist is sure all research avenues have been explored, and the product manager is sure that a valid product cannot be built around existing performance, it might be time to move on to another project. Do not underestimate the ability to identify an unsalvageable project and the courage to make the decision to end it; it is a crucial part of the fail-fast methodology.

3.4. KPIs check

If the predetermined hard metric is the only KPI and captures all product needs exactly, then this phase can be more of a formality, when the final model is presented and the development phase is declared over. This is usually not the case.

In the more common case, the hard metric is a good approximation of the actual product needs, but not a perfect one. This phase is thus an opportunity to make sure that the softer metrics, that cannot be checked automatically, are also satisfied. This is done together with product and customer success. If you can additionally check the actual value to a customer directly— e.g. when working with a design partner — then it’s the best guide you could find for your iterations.

For example, let’s say that we’re dealing with a complex task such extracting relevant documents, given a query, from a huge corpus. The team might have decided that to try and increase the quality of the result set, focusing on variance in content and topics of the returned documents, as clients feel the systems tends to cluster quite similar documents in top results.

Model development might have progressed with some measurable metric for content variance in the results set — each model is scored by how varied are the top 20 documents it returns, given a set of test queries; perhaps you measure overall distance between document topics in some topic vector space, or just the number of unique topics or flatness of significant word distributions.

Even when the data scientist settles on a model which improves this metric significantly, product and customer success people should definitely take a look at the actual results for a significant sample of the test queries; they might find problems hard to quantify, but possible to solve, such as a model increasing result variance by pushing up some recurring non-relevant topic, or by including results on similar topics but from different sources (e.g. news article vs tweets, which use a very different language).

When the product person is convinced the model answers the stated goals of the project (to a satisfactory degree), the team can move forward to productizing it.

4. The Deployment Phase

4.1. Solution Productization & Monitoring Setup

This phase, as mentioned earlier, depends on the approach to both data science research and model serving in the company, as well as several key technical factors.

Productization: In cases where research language can be used in production, this phase might entail adapting the model code to work in a scalable manner; how simple or complex this process is depends both on distributive computing support for the model language, and the specific libraries and custom code used.

When research and production language are different, this might also involve wrapping the model code in a production language wrapper, compiling it to a low level binary or implementing the same logic in production language (or finding such an implementation).

Scaleable data ingestion and processing also need to be set up, in the (quite common) case where this was not part of the model. This can mean, for example, turning Python functions that ran on a single core to a pipeline streaming data goes through, or into batch jobs running periodically. In the case of significant data re-use, a caching layer is sometimes set up.

Monitoring: Finally, a way to continuously monitor the performance of the model is set up; in rare cases, when the source of production data is constant, this can perhaps be safely skipped, but I’d say that in most cases you can’t be sure of the stability of the source data distribution. Setting up such a performance check, then, can help us to not only detect problems in the model that we might have missed during development and productization, but more importantly changes in the source data distribution above which the model operates — commonly referred to as a covariate shift — that can degrade, in time, the performance of a perfectly good model.

Take, for example, the case where our product is an app that detects skin marks and evaluate whether to recommend the user to go see a skin doctor. A covariate shift might happen in our data when a popular new phone goes to market, equipped with a camera significantly different from those present in our data.

4.2. Solution Deployment

If everything is set up correctly, then this stage can sum up to, hopefully, pushing a button to deploy the new model — and any code serving it — to the company’s production environment.

Partial Deployment: It is possible, however, that in order to test the effectiveness of the model (for example, in reducing churn, or increasing average monthly spending per user), the model will be deployed to in a manner that only part of the user/customer base is exposed to it. This enables a direct comparison of the effect on any measurable KPIs between the two (or more) groups in the user base.

Another reason you might not want to deploy the model to everyone is if it was developed to answer the needs of a specific customer or a group of customers, or if it’s a premium feature or part of a specific plan. Alternatively, the model might have some element of personalization per user or customer; this is can sometimes be achieved by actually having a single model which take customer characteristics into account, but sometimes entails actually training and deploying a different model for each customer.

Whatever the case, all these scenarios increase the complexity of deploying the model, and depending on existing infrastructure in the company (e.g. if you’re already deploying some of the product features to subsets of your customers) they might require a significant amount of additional development by your back-end team.

This phase is even more complex when the model is to be deployed on end-products, like user phones or wearables, in which case model deployment might only happen as part of the next app or firmware update deployed.

Generating Bias: Finally, all cases of partial deployment are actually a pressing issue to the data science team for another reason: this naturally introduces bias into the future data the model will start accumulating — the model will start operating on data by a subset of users with possibly unique characteristics. Depending on the product and the specific biased characteristics, this can have a big impact on the performance of the model in the wild, and possibly on future models trained on data accumulated during this period.

For example, in the case of device update, users who updated their apps/firmware earlier tend to fall into certain demographics (younger, more tech-savvy, higher income, etc.).

4.3. KPIs check

I’ve added another KPIs check here because I think a solution cannot be marked as delivered before its performance and successful answering of product and customer needs has been validated after deployment and actual use.

This might mean sifting through and running analysis on the resulting data a couple of weeks after deployment. When actual customers are involved, however, this must also involve product or customers success people sitting with the customers and trying to understand the actual impact the model has on their use of the product.

4.4. Solution delivered

Users and customers are happy. Product people have managed to build or adapt the product they wanted around the model. We’re done. Toasts are toasted, cheers are cheered, and all is well.

The solution is delivered, and I would call the project done at this point. It does, however, keeps on living in a specific way — maintenance.

Maintenance

Having set up health checks and continuous performance monitoring for the model, these can trigger up short bursts of working on the project.

When something seems to be suspicious, we usually start by looking at the data (e.g. for covariate shifts), and perhaps simulating the response of the model to various cases that we suspect cause the problem. The results of these checks can send us into anything between a few hours of small code changes and re-training of the model and full model development iterations (as reflected in the figure opening this post), with severe cases sometimes entailing going back to the research phase to try completely different directions.

Final Words

This is a suggestion for the flow of data science projects. It is also very specific, limited in scope — for the sake of simplicity and visibility — and obviously cannot cover the many variations on this flow that exist in practice. It also represents my experience.

For all of these reasons, I’d love to hear your feedback, insights and experience from running, leading or managing data science projects, whatever their size, and whatever the size of the data science team you are part of.