Containers are hugely helpful for improving security, reproducibility, and scalability in software development and data science. Their rise is one of the most important trends in technology today.

Docker is a platform to develop, deploy, and run applications inside containers. Docker is essentially synonymous with containerization. If you’re a current or aspiring software developer or data scientist, Docker is in your future.

Don’t fret if you aren’t yet up to speed — this article will help you understand the conceptual landscape — and you’ll get to make some pizza along the way.

In the next five articles in this series we’ll jump into Docker terms, Dockerfiles, Docker images, Docker commands, and data storage. By the end of the series (and with a little practice) you should know enough Docker to be useful.

Docker Metaphors

First, I’m going to shed some light on Docker metaphors.

They’re everywhere! Just check out this book..

Google’s second definition for Metaphor is what we want:

a thing regarded as representative or symbolic of something else, especially something abstract.

Metaphors help us make sense of new things. For example, the metaphor of a physical container helps us quickly grasp the essence of a virtual container.

A physical container

Container

Like a physical plastic container, a Docker container:

- Holds things — Something is either inside the container or outside the container.

- Is portable — It can be used on your local machine, your coworker’s machine, or a cloud provider’s servers (e.g. AWS). Sort of like that box of childhood knickknacks you keep moving with you from home to home.

- Has clear interfaces for access — Our physical container has a lid for opening and putting things in and taking things out. Similarly, a Docker container has several mechanisms for interfacing with the outside world. It has ports that can be opened for interacting through the browser. You can configure it to interact with data through the command line.

- Can be obtained from a remote location — You can get another empty plastic container from Amazon.com when you need it. Amazon gets its plastic containers from manufacturers who stamp them out by the thousands from a single mold. In the case of a Docker container, an offsite registry keeps an image, which is like a mold, for your container. Then when you need a container you can make one from the image.

Unlike a virtual Docker container, a new plastic container from Amazon will cost you money and won’t come with a copy of your goods inside. .

Living Instance

A second way you can think of a Docker container is as an instance of a living thing. An instance is something that exists in some form. It’s not just code. It’s code that has brought something to life. Like other living things, the instance will eventually die — meaning the container will shut down.

An instance of a monster

A Docker container is a Docker image brought to life.

Software

In addition to the container metaphor and the living instance metaphor, you can think of a Docker container as a software program. After all, it is software. At its most basic level, a container is a set of instructions that manipulate other bits.

Containers are code

While a Docker container is running, it generally has programs running inside it. The programs in a container perform actions so your application will do something.

For example, the code in a Docker container might have sent you the content you are reading on this webpage right now. Or it might take your voice command to Amazon Alexa and decode it into instructions another program in a different container will use.

With Docker you can run multiple containers simultaneously on a host machine. And like other software programs, Docker containers can be run, inspected, stopped, and deleted.

Concepts

Virtual Machines

Virtual machines are the precursors to Docker containers. Virtual machines also isolate an application and its dependencies. However, Docker containers are superior to virtual machines because they take fewer resources, are very portable, and are faster to spin up. Check out this article for a great discussion of the similarities and differences.

Docker Image

I mentioned images above. What’s an image? I’m glad you asked! The meaning of the term image in the context of Docker doesn’t map all that well to a physical image.

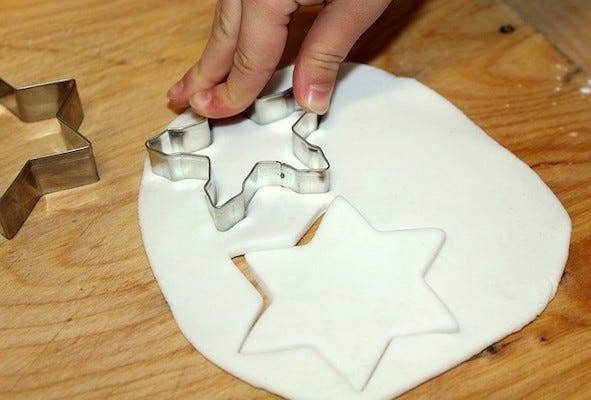

Images

Docker images are more like blueprints, cookie cutters, or molds. Images are the immutable master template that is used to pump out containers that are all exactly alike.

Cookie cutters

An image contains the Dockerfile, libraries, and code your application needs to run, all bundled together.

Dockerfile

A Dockerfile is a file with instructions for how Docker should build your image.

The Dockerfile refers to a base image that is used to build the initial image layer. Popular official base images include python, ubuntu, and alpine.

Additional layers can then be stacked on top of the base image layers, according to the instructions in the Dockerfile. For example, a Dockerfile for a machine learning application could tell Docker to add NumPy, Pandas, and Scikit-learn in an intermediate layer.

Finally, a thin, writable layer is stacked on top of the other layers according to the Dockerfile code. (You understand that a thin layer is small in size because you intuitively understand the thin metaphor, right?)

I’ll explore Dockerfiles in more depth in future articles in this series.

Docker Container

A Docker image plus the command docker run image_name creates and starts a container from an image.

Container Registry

If you want other people to be able to make containers from your image, you send the image to a container registry. Docker Hub is the largest registry and the default.

Phew! That’s a lot of pieces. Let’s put this all together in terms of making a pizza.

Cooking with Docker

Landscape Metaphor

- The recipe is like the Dockerfile. It tells you what to do to get to your end goal.

- The ingredients are the layers. You’ve got crust, sauce, and cheese for this pizza.

Think of the recipe and the ingredients combined as an all-in-one pizza-making-kit. It’s the Docker image.

The recipe (Dockerfile) tells us what we’re going to do. Here’s the plan:

- The crust is preformed and immutable, it’s like a basic ubuntu parent image. It’s the bottom layer and gets built first.

- Then you’ll add some cheese. Adding this second layer to the pizza is like installing an external library — for example NumPy.

- Then you’ll sprinkle on some basil. The basil is like the code in a file that you wrote to run your app.

Alright, let’s get cooking.

Oven

The oven that bakes the pizza is like the Docker platform. You installed the oven into your house when you moved in so you could make things with it. Similarly, you installed Docker onto your computer so you could cook up containers.

- You start your oven by turning a knob. The

docker run image_namecommand is like your knob — it creates and starts your container. - The cooked pizza is like a Docker container.

- Eating pizza is like using your app.

Like making a pizza, making an app in a Docker container takes some work, but in the end, you have something great.

Wrap

That’s the conceptual framework. In Part 2 of this series, I clarify some of the terms you’ll see in the Docker ecosystem. Follow me to make sure you don’t miss it!

Hopefully, this overview has helped you better understand the Docker landscape. I also hope it has also opened your eyes to the value of metaphors in understanding new technologies.