This blog post is an overview of quantum machine learning written by the author of the paper Bayesian deep learning on a quantum computer. In it, we explore the application of machine learning in the quantum computing space. The authors of this paper hope that the results of the experiment help influence the future development of quantum machine learning.

With no shortage of research problems, education programs, and demand for talent, machine learning is one of the hottest topics in technology today. Parallel to the success of learning algorithms, the development of quantum computing hardware has accelerated over the last few years. In fact, we are at the threshold of achieving a quantum advantage, that is, a speed or other performance boost over classical algorithms, in certain specific application areas – machine learning being one of them. This sounds exciting, but don’t ditch your GPU cluster just yet; quantum computers and your parallel processing units solve different classes of problems.

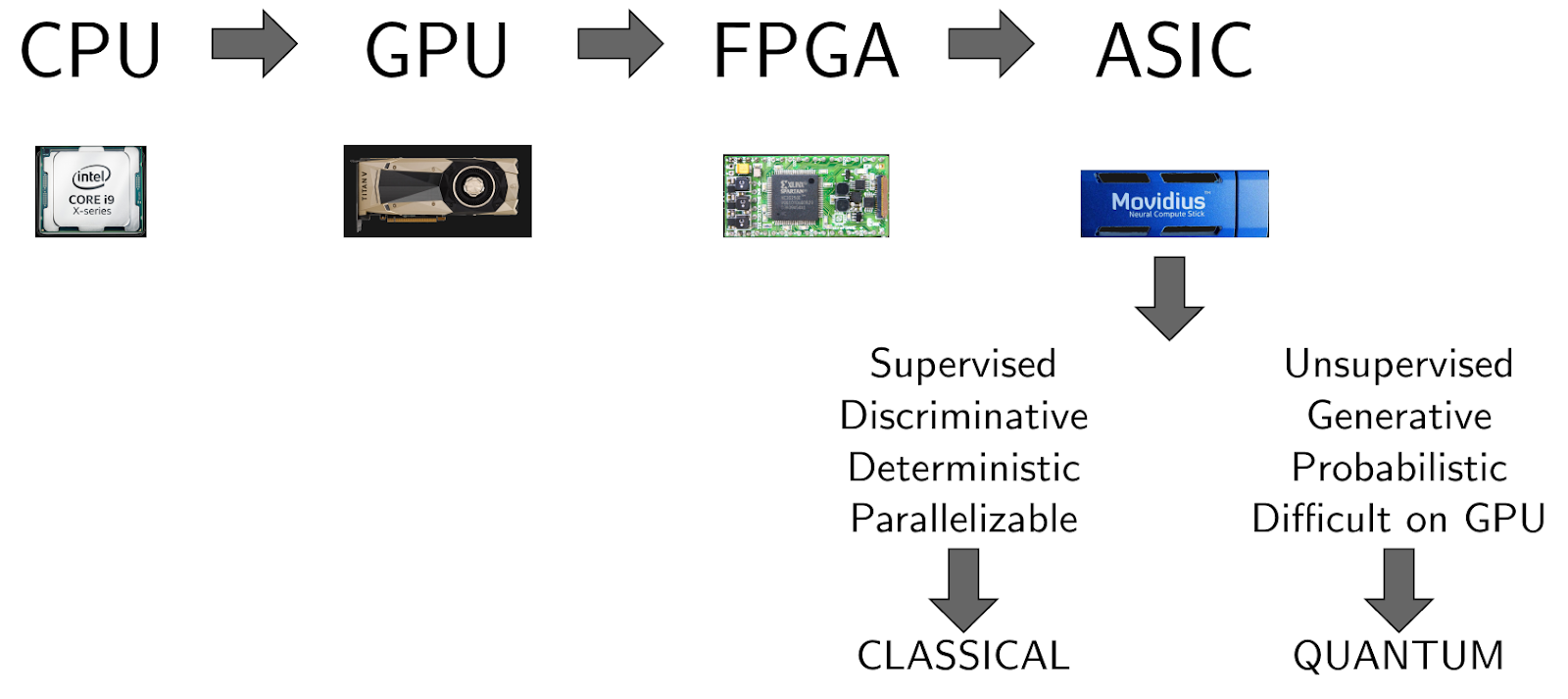

If you look at the figure below, you’ll get a quick idea of how to think about the role of quantum computing in machine learning. As the complexities of the problems to be solved have grown, AI stacks have begun to include more and more different hardware back-ends, including anything from off-the-shelf CPUs to Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) and neuromorphic chips. Yet, there are still problems that remain too difficult to solve: some of these are amenable to quantum computing. In other words, quantum computers can enable the creation of more complex machine learning and deep learning models in the same way that GPUs have done in the past.

Figure 1. AI already uses a heterogeneous mix of hardware back-ends. In the future, this blend will incorporate quantum technologies that enable certain learning algorithms. Based on a talk by Steve Jurvetson at the Machine Learning and the Market for Intelligence Conference.A quantum computer uses “quantum bits” (qubits): a qubit is a special probability distribution between 0 and 1. The number of qubits and the quality (the fidelity) of the operations that we can perform are the most important indicators of how good a quantum computer is. Quantum machine learning uses quantum computers to run certain parts of a learning algorithm. The near-term feasibility of the various quantum machine learning proposals varies. Some quantum algorithms can already be run on current quantum hardware (e.g., algorithms that need few qubits and gates, so-called variational algorithms), others need better quantum computers, with a lot more and higher quality qubits (such as the most famous algorithms like factorization by Shor’s algorithm or unstructured search by Grover’s algorithm). So far, only a handful of benchmark results are available for running actual quantum machine learning algorithms on real hardware.

All of these benchmarks focus on the more obvious classes of algorithms that were designed for these noisy, early quantum devices. We were interested in the other extreme: let’s take one of the hardest algorithmic primitives (algorithms where all the steps are basic operations and do not make calls to other algorithms) and see what kind of results we can get. Why? A well-known algorithm is the quantum matrix inversion algorithm (HHL for short after the authors of the original article), which offers an exponential speedup in matrix inversion compared to classical algorithms, is one of the most common algorithmic primitives in quantum machine learning. We believed that there were advantages in using quantum computers, but we also believed that we had to factor in what the current quantum hardware is capable of. So we set out on a quest to show how bad things can get.

Countless caveats apply with the quantum matrix inversion algorithm: it requires quantum circuits that have thousands of error-corrected qubits and an even larger number of gates. In other words, it needs a perfect, large-scale, universal quantum computer. This is a stark contrast to the handful of noisy qubits we have today and the shallow circuits we can build given the short times the qubits can maintain superpositions (also known as coherence time). The superposition is the special probability distribution between 0 and 1 that we mentioned earlier. If the coherence time is bad, the probability distribution is not under our control: we cannot perform transformations on it to express a calculation.

Given that quantum matrix inversion is a common subroutine in quantum machine learning and it requires very high-quality quantum computers, we wanted to tell a cautionary tale. We found an opportunity: two papers appeared in late 2017 that made a connection between deep learning and Gaussian processes. This is an important feat since combining deep learning with Bayesian techniques (of which Gaussian processes is an example) allows for getting much more information from the network. In particular, it provides easy ways of knowing the uncertainty associated with a prediction. Unfortunately, Bayesian learning is hard, even with the best classical hardware. That is why, exploiting this new-found connection, we came up with a new quantum Bayesian deep learning protocol that internally used quantum matrix inversion for achieving a speedup. On the surface, the new protocol looks good: it is a problem that is hard to solve classically, we applied some mathematical tricks, and we could give it a significant lift in speed by using a quantum algorithm! Unfortunately, this speedup requires very, very high-quality quantum computers.

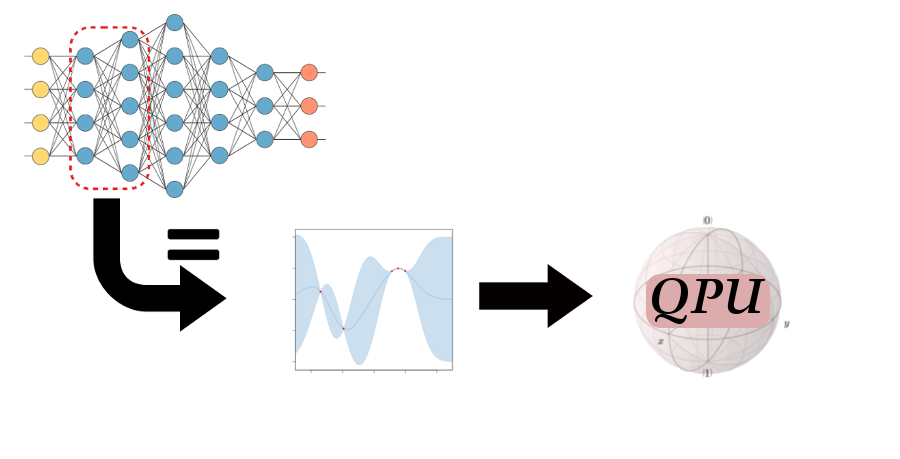

We used this opportunity to implement the quantum matrix inversion algorithm and benchmark it on contemporary quantum computers. The corresponding paper has just been published (the open version can be found on arXiv), with a matching git repository. The figure below gives an overview of what we proposed.

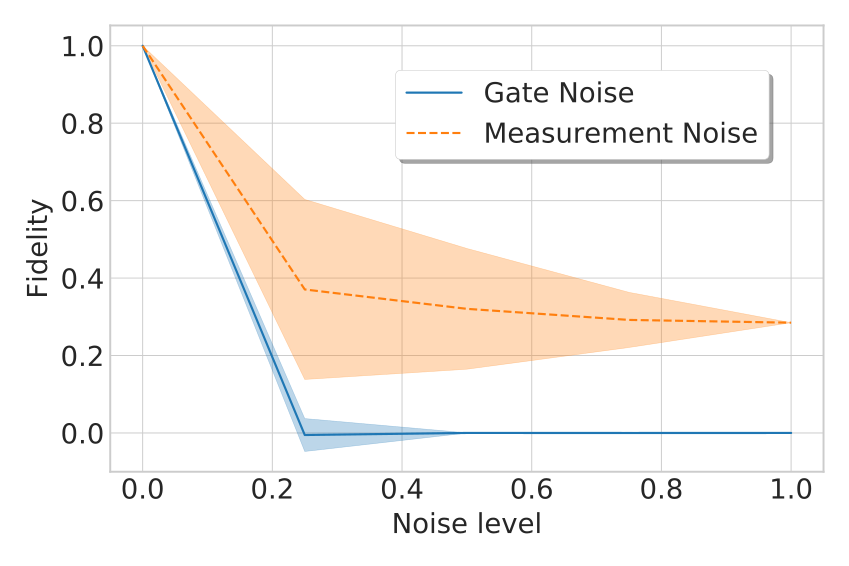

Figure 2. Schematic overview of quantum Bayesian deep learning. A layer of neurons in a neural network can be considered equivalent to a Gaussian process under certain conditions. Recent work showed that the equivalence still holds if we consider many layers. To train the Gaussian process fast, we use the quantum-assisted protocol and run it on a quantum processing unit. Image credit: Alejandro Pozas-Kerstjens.The results confirmed that despite its widespread usage, quantum matrix inversion is not the first target for achieving a real-world quantum advantage. Any gate noise immediately destroys the calculations, which is intuitive, since we need dozens of gates for even a small matrix inversion. Reading out the result of a quantum computation is done through measurements on the device. Faults in the devices measuring the qubits also affect the performance of the algorithm, however, as there are few measurements to be done, this source of error has a smaller impact.

Figure 3. Fidelity of final state after inverting a 4×4 matrix. Simulations using different noise levels and noise models.To run on real hardware, we needed a simplification, because the full-blown algorithm was too deep even for a 2×2 matrix. Fortunately, we found just what we needed: a shallow circuit specifically designed for inverting 2×2 matrices. While this is not relevant for any practical application, this circuit has slightly over a dozen gates (including state preparation) and interesting results. We used both the 16-qubit IBM chip and the 8-qubit Agave chip by Rigetti. The Agave chip has a specific linear topology, that introduces a handful of extra gates for operating the quantum state as desired. The IBM QPU ran with an 89% success rate after measurement, which translates to about 0.78 fidelity with the correct target state. The Agave QPU achieved a 50% success rate, which translates to zero fidelity, but we believe this is mainly because of the linear topology and the extra gates that need to be inserted. These are not many, but enough to make the execution of the algorithm take longer than the coherence time of the qubits.

There is no point in creating a QML algorithm for something that can be efficiently done on a GPU cluster. As Bayesian deep learning is difficult to execute when using classical resources, we attacked it with quantum protocols. With this theory, we have made non-trivial advances towards allowing quantum computers to train deep neural networks.

On the implementation side, we have established a complete implementation of the quantum matrix inversion algorithm, which can serve as a hard benchmark for future quantum computers. We concluded that it is better to stay away from these abstract algorithms and pay more attention to the limits of the quantum hardware of today. We hope that the classical and the quantum machine learning communities will find the results intriguing and that the next generation of quantum coders can learn from this experiment.

This article has originally appeared on AISC.