Ready to learn Artificial Intelligence? Browse courses like Uncertain Knowledge and Reasoning in Artificial Intelligence developed by industry thought leaders and Experfy in Harvard Innovation Lab.

After discovering the amazing power of convolutional neural networks for image recognition in part five of this series, I decided to dive head first into Natural language Processing or NLP. (If you missed the earlier articles, be sure to check them out: part 1, part 2, part3, part4, part5, and part6.)

This hotbed of machine learning research teaches computers to understand how people talk. When you ask Siri or the Google Assistant a question, it’s NLP that drives the conversation. Of course, as an author of novels and articles, working with language seemed like the obvious next step for me.

I may suck at math but words are my domain!

So I set out to uncover what insights NLP could give me about my own area of mastery.

Behold the Bard!

I had so many questions. Had NLP uncovered the hidden keys to writing heart-wrenching poems? Could AIs turn phrases better than the Bard? Could they elucidate the secret to writing compulsively clickable headlines?

Luckily, I had just the right project in mind to test the limits of NLP. I was in the midst of naming the second book in my epic sci-fi saga The Jasmine Wars but I’d struggled to find the perfect title. So I wondered:

What if I could feed a neural net with the greatest titles of all time and have it deliver a title for the ages?

This isn’t my first foray into computer assisted title generation. There are a number of random title generators out on the interwebs that I’ve tried from time to time.

Frankly, they’re not very good.

They’re the type of toy you play with for a few minutes and then move on. They work by randomly slamming words together or by iterating through a few basic permutations like “The _______ of _________.” I seriously doubt a single author actually selected his or her title from the primordial word soup these engines produce.

Throwing words into a hat, shaking it up and pulling them out won’t get you very far. A million monkeys typing randomly on keyboards might make Shakespeare in a million years, but I don’t have that kind of time.

AI to the rescue!

Networks that Peer into the Depths of Time

As we learned in part five, neural networks hold amazing power because they do automatic feature extraction. We can’t tell a machine all the steps we take to drive a car but we can let it figure it out all by itself!

As an author I use all kinds of tricks to capture people’s attention but trying to boil those down to a set of rules is virtually impossible. It goes well beyond simply understanding nouns, verbs and adjectives. There’s a rhythm to language. Words can spark fiery images in your mind. They can overwhelm you with emotion, making you break down with tears or get you quivering with anticipation. They create sound and fury, movement and feeling.

Can a machine do all of that?

Am I on the chopping block of automation?

Will AI make writers redundant in the future?

To find out, I first needed to figure out what kind of neural network (NN) I needed. NNs are very specific to the problem they’re trying to solve. Humans might posses a universal learning algorithm but we certainly don’t know it yet. The current state of the art focuses on “narrow AI” with each neural net doing some things well and other things really badly.

So what kind of NN helps us understand language?

Hands down the dominant force behind NLP are Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), in particular Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) RNNs.

So let’s take a look at these and see if they can help me unlock the secrets of blockbuster title creation.

The Magic of Recurrent Neural Nets

Inevitably, when you start looking into RNN’s you discover OpenAI researcher Andrej Karpahy’s blog “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks.” The title alone filled me with tremendous hope.

Just how unreasonably effective are these amazing systems?

If the title didn’t get me, the first line surely did:

“There’s something magical about Recurrent Neural Networks?”

Magical!

I knew a fantastic title couldn’t be far off, its supernatural power already swirling in the hidden depths of the matrix.

So what makes RNN’s “magical?” First, they’re particularly adept at predicting the future.

When you buy a stock or pick someone up at the airport, you’re making a guess about the future. A baseball player trying to snag a fly ball has to predict the arc of the ball and leap to where it’s going to catch it.

We make predictions all the time, whether we’re weaving our way through big city foot traffic or driving a car.

Are those other cars going to hit you?

Is someone veering into your lane?

Where will your friend be waiting for you at the airport?

We’re constantly trying to predict what happens next and react to it ahead of time so we’re ready. RNN’s do the same thing by analyzing time series data.

They can look forward and unlike most other NN’s they can look back too. They have a “memory” of events past. They can see the trajectory of a rocket or a stock price move and predict a buy or sell. When it comes to self-driving cars they can predict trajectories and arcs, which means they can help prevent accidents (as you see in the footage of a Tesla chiming a warning before a crash) or when to take an off ramp.

They’re also good at working with sequences of arbitrary length. That’s unique because most NN’s can only take fixed size vectors/tensors and output fixed size vectors. With convolutional neural nets we have to munge our images into a certain shape to make them work. But that’s a no go for text. You can’t take a novel or the entirety of Wikipedia and jam it into a one size fits all box. This flexibility makes RNNs great for NLP, which encompasses everything from machine translation to sentiment analysis to Google’s Pixel AIunderstanding your questions.

This even gives RNN’s a level of “creativity.” Check out this article on generating music with RNNs. The system is trained on a series of musical sequences and “makes” music by predicting the likely next sequences.

What else can RNNs do?

If we were doing sentiment analysis, aka trying trying to figure out if people are feeling good or bad about something, then we could feed it movie reviews and have it output a binary classification score from love (1) to hate (-1).

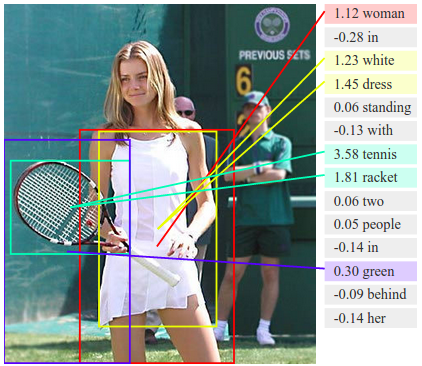

You could also feed it a single input and have it deliver a series of outputs. For example, we could feed the network an image (single input) and have it generate a text summary of images (series of outputs). Check out this article that shows how RNNs look at pictures and deliver summaries like “Boy doing a backflip off a wakeboard.”

The system locates objects and tries to create a sentence from that, like we see with this gal playing tennis.

We could also feed it a sequence to vector network, called an encoder and output the reverse, a vector to sequence, which we call a decoder.

This is useful for machine translation (as seen in this awesome article from the Machine Learning is Fun dude). Google recently used RNNs to revamp their Google Translate system into something that blows away the gobbledygook translations of previous versions, delivering human level translation capabilities. And on April 11, 2017, Google finally open sourced the model behind their translation engine, called tf-seq2seq (not the best marketing name but hey, we’ll take it.) Basically what we do is train the network with both the original text and a professionally translated text in another language (the input and output) and then use that to help the machine translate fresh documents it’s never seen.

But for our purposes we need one very specific feature of RNN’s:

They’re great at generating text.

It’s also what Karpahy’s “magical RNN” blog is about and what got me interested.

Let’s take a quick look at how RNN’s work and then leap into how I attempted to use them to generate my next great American novel title.

Time After Time

Recurrent Nets look a lot like feed forward neural nets, except they also have connections that point backwards. If we look at a simple single neuron RNN, we can see that it receives inputs X at a particular point in time, which we call a “frame” as well as an output from the previous step Y(t-1).

The network is really a series of steps in time. It’s no coincidence that each step is called a frame, because it’s like the frame in a film. We “unroll the network” through time, just as we play a movie on the silver screen.

Time is represented by “t”. The current moment in time is just “t” which we see in the middle frame. The previous step is “t-1” (on the left) and one step into the future is “t+1” (the right). The s in the middle is the hidden state, hence the “s” for state. It is the memory of the cell. In pure feed-forward networks the inputs are just the weighted outputs of previous nodes. In a RNN, this also includes the weighted outputs from a previous time step. In other words, like we said earlier, it can look back in time and it can attempt to predict a future step.

Developing Long Term Memory

Basic RNNs have a few challenges. One of the main challenges with plain old RNN’s is that if the network is too deep it can easily begin to “forget” information from earlier parts of the time sequence.

Why is that an issue?

Well let’s pretend you have a RNN doing sentiment analysis of news about stocks, looking to generate buy or sell signals based on whether the public is bullish or bearish on a stock. A stock blogger may start off telling you to sell in the first sentence and then spend the rest of the article lauding the future buy potential of the stock once it has a few weeks to recover from whatever news is damaging the stock today. The system may forget the “sell” part and declare it a strong “buy” based on the positive sentiment later in the story.

They can also have difficulties learning long range dependencies even over shorter sequences. That becomes a serious problem in NLP because the meaning of a sentence isn’t always clustered closely together.

Most people don’t produce sentences that would make their grade school grammar teacher proud. Instead they scatter the meaning all over the sentence. They use screwy grammar and slang. For humans this is no problem. We have the remarkable ability to understand sentences that are all jacked up. Misplaced modifiers, missing words, typos, and dangling participles won’t slow us down but they can really trip up machines.

For example, if I say “The man in the blue blazer and white cap played a brilliant jazz solo”, the point of the sentence is not what the man is wearing, which is close to the subject of the sentence but that he played a brilliant jazz solo. If the system forgets that information by the time it gets to the music it missed the point.

This is what’s know as the vanishing gradients problem which Stanford’s awesome deep learning and NLP class goes into at length.

But I’ll save you a lot of reading and give you a quick summary here. To understand vanishing gradients you need to understand a bit about backpropagation. In part five we talked about how backpropagation looked to minimize errors by working to the lowest point on the error landscape. That helps the neural network adjust its weights so that it can go to the next epoch of training. It looks like this in 3D:

In some ways it is easier to understand in 2D though, so let’s see that:

The system is taking tiny steps, as it tries to work its way to the bottom of the curve. Now, that’s all well and good when you have a clean error landscape with a nice well-defined curve. But what if the curve flattens out badly? Let’s take a look.

Courtesy of the Stanford Deep NLP course

When the line flattens out we call the neurons “saturated.” Instead of activating and finding useful data, they are effectively dead. Even worse, they have an exponentially bad effect on previous neurons. Remember that neural networks are matrices, which are really just spreadsheets on steroids. One cell is added or multiplied to the next cell in a long chain of equations.

By the way, if you’re still struggling with matrix math, I am loving this anime book called The Manga Guide to Linear Algebra.

The Japanese just have better teaching tools. If I had this book in school I might have enjoyed it a lot more.

Back to the math!

Remember our dot product image from part six on math notation?

Now imagine all of those numbers are zero or almost zero. What happens to the chain of calculations?

When a number of neurons have small numbers as their value, the multiplication causes the gradient values to shrink exponentially fast, which quickly drives all the neurons in the chain towards zero. This means they’re effectively turned off and doing nothing. They’re like dead pixels on a TV screen, no longer useful. The deeper the network the worse this problem gets.

A number of solutions to this problem cropped up over the years. The first was to use the RELU activation function instead of the Tanh or Sigmoid activation functions.

Why do that? Well you just have to look at a Sigmoid curve to understand.

Notice how it has that nice curved edge at the bottom and top? We want curves like that when we’re drawing a face or the arch of a bridge, but that bottom curve is the slope of despair when it comes to vanishing gradients.

Now look at a RELU vs Sigmoid visualization:

Notice that hard angle! The RELU function delivers a constant of 0 or 1 and as you can see it has a hard shape with no soft slope at the edges, so it isn’t as likely to hit that vanishing problem.

But there’s a better solution. Let’s check that out.

Enter the Dragon

The real answer to the question of vanishing gradients is not to change the activations on a regular RNN.

It’s to switch to the more popular Long Short Term Memory (LSTM), first outlined in 1997, or Gated Recurrent Networks (GRUs), outlined in 2014.

Both of these architectures were designed with vanishing gradients in mind. They were also meant to look for long range dependencies. In practice regular RNNs are rarely used anymore, while GRUs and LSTMs dominate the field.

The name LSTM might seem strange at first but not when you consider what the network is doing. In essence an LSTM is a black box memory cell that looks like a standard RNN memory cell but in reality it holds dual states in two vectors, a long term state and a short term state.

Here is an illustration of an LSTM from my friends over at the Deep Learning 4 J team.

By the way, one of the absolute best books I’ve read on this topic (and neural nets/deep learning in general) is the just released Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and Tensorflow. I saw a few earlier editions and they really upped my game. Don’t wait, just grab it ASAP. It rocks. It goes into a ton more detail than I have here but I’ll give you the basics to get you moving in the right direction fast.

You can see that information travels along two lines through a series of “gates.” The top line is called the “forget line.” This is a pretty piss poor term, in my humble opinion, but I didn’t name it, so don’t blame me. Let’s just go with it.

The “forget line” remembers the long term state.

It gets copied forward into new cells as the network unrolls. Actually, it’s not a completely ridiculous name.

It’s called the forget line because it does loose bits of information as it goes.

The other lines contain short term associations and memories, which are then incorporated into the “forget” line.

At each time step some memories go out the window and some get added.

GRU’s are basically a simplified form of LSTMs. Check out this awesome diagram of a GRU from Jacob Kvita, a comp-sci student and former Red Hatter, who made them for his thesis.

What’s the difference?

The GRU cell merges the long and short term memory into a single vector.

Why do that? Simple. Performance. It’s less computationally expensive andyet somehow seems to perform as well. That’s a win!

It also uses only a single “gate” for both the short and long term memory. Lastly, it adds a new kind of gate that decides what to show to the next layer.

Monkeys in the Machine

OK. All that’s great, Dan, but how do I generate text from that?

Good question.

Karpathy’s post demonstrates a “character” level RNN. A character level model looks to understand language on a character by character basis.

How does it do that?

All neural networks are essentially complicated prediction engines. So we feed the system millions words and it stores those words as sequences of characters. Then it begins to predict what the next character is likely to be. Once it’s learned what to predict we can then have the system pull tricks for us like generate sample text based on feeding it a “seed” set of words. That’s all theoretical, so let’s look at a simple example.

First, let’s pretend that the system has only learned a few words:

- hey

- hello

- help

- I

- there

- need

We also teach it a few punctuation marks like “.” and “!”

Remember though that our simple RNN hasn’t learned complete words. It’s only learned a series of characters, so instead of understanding “hello” as an entire self contained entity, it knows h-e-l-l-o. In knows that “e” follows “h” and so on.

Now imagine that I show the system a million variants of sentences that I can construct from the few vocabulary words that I’ve taught the machine. Those sentences might be something like:

- Hey, there. Hello!

- Hello! Help!

- Help!

- Help.

I then seed the engine with the phrase:

- “I need he”

Notice that I didn’t write the complete word that I want it to guess.

The system would then look inside its black box and try to predict the next likely character. In this case it could be either “l” as in “hello” or it could be “y” as in “hey” or it could be “l” as in “help.”

If the network is properly trained we hope it chooses “l” and eventually “p” for “help” because that’s one of the few constructions that make sense.

We can find a character level RNN implementation in the Keras examples Github.

It’s trained on a corpus of Nietzsche with about 100,000 words. The example recommends that we use at least a million words to make the system more robust.

I decided to feed my character level RNN a dataset that I created by hand over a few days which you can find on my Github. I typed in every single great novel title by combing through my memory, bookshelf, and numerous top 100 lists.

Unfortunately, I quickly ran out of great book titles.

One option would be to simply feed it as many titles as I could find by downloading library catalogs, but I wanted to focus on titles that really stood out and not clog it up with any old crap. To augment it I went on to great movie titles, then great songs and band names.

Still when I was done, I was left with a mere 26K worth of words, which made the system particularly unreliable. But I decided to give it a go anyway. So how did it do? Here are few results.

tha ect are dog

a9t byta go than

wel pt year benc

Hardly magical.

Even after training the system for many, many, many epochs it still mostly sucked. I ran the system for 7000 iterations overnight. It still produced garbage.

At this point I couldn’t tell whether it was just the tiny dataset that I gave it or the RNN itself. Rather than brute force tweak the system, I decided to see if I could find an answer to that question before spending five nights tuning the system to no end. As I puzzled over why it failed, I turned back to Karpathy’s blog and found a potential answer.

Karpathy trained his character level generator on Shakespeare, with significantly more text for the machine to eat up. Here is an example from his post:

“PANDARUS: Alas, I think he shall be come approached and the day When little srain would be attain'd into being never fed, And who is but a chain and subjects of his death, I should not sleep.Second Senator: They are away this miseries, produced upon my soul, Breaking and strongly should be buried, when I perish The earth and thoughts of many states.”

He’s particularly excited that the system seems to be generating text that looks like Shakespeare, at least a first glance.

It is formatted like a play. There is dialogue. There are character names. It even has a little flavor of the Bard with words like “alas.”

In some respects this is truly amazing. Remember that the system doesn’t know anything about English. It has no context. It has no knowledge of verbs or characters or dialogue at all. It learned that through grokking the patterns and outputting a similar pattern.

However, as a writer, I found myself less enamored with this output than Karpathy.

While it’s true that the system aped the basic formatting of a play, I don’t see this as much of a feat. We had dumb systems capable of auto-formatting a play in 1980’s for screenwriters. The biggest thing I notice is that the system produced gibberish that’s formatted nicely, but that means absolutely nothing. It produces words, but the words put together add up to zilch. The sentences mean nada.

Basically, it detected a pattern but not a very useful one. I wanted it to learn poetry and it learned how to act like a sort of smart version of Screenwriter Pro.

But I didn’t lose hope!

Intuitively, I recognized that it makes little sense to try to train these systems at the character level.

Why make the system work so hard to try to predict what the next character should be so as to form some semblance of words?

Notice that even in the Shakespeare output it sometimes produced nonsense words like “srain” which means that even after hours of training it was still struggling to avoid kindergarten level mistakes. I wondered if researchers realized, like I did, that it made more sense to train the system at the “word” level or even the “sentence” level. In other words, instead of studying “h-e-l-l-o” train it on “hello”.

Turns out they did.

I discovered this modification of the basic character RNN, turning it into a word level monster. This system also introduced the more advanced concepts of LSTM and GRUs. Awesome! Now the system can learn whole words, instead of letters.

And in a testament to just how fast this field is developing, there are dozens of word level RNN systems, since I started this article three months ago. I had some other work take precedence, and some of the earlier Learning AI articles seemed to fit better if they came first, so I set this article aside. Now I come back to find a number of different versions of word level RNNs for you to play with and test out. Sweet!

So did it work? Here’s some output after training the system for thousands of epochs, again remembering that my dataset is far from the ideal size.

It outputs a giant block of text that is a little hard to deal with, so I wrote a little script to slice it up into 2 to 7 word sentences, which is about the length of a good title. Most good titles actually live in the four word range.

That gave me some good results that I saved to a file, discarding the obvious gibberish ones.

Delicatessen in the Jungle

Daisy the Cloudy Shoplifters

Waiting for a Glass Full

Blood Agency

The China Proposal

Beloved Mayor of Horton

Walking China

The Metropolis Jacket

The Steel Beowulf

Magnolias Dawn, Little Prarie Sun

Fried Castle Blind

Sense of Disobedience

The Meatballs Dune

China Hooker Tomatoes

Of Slave Blood

In the Usual House

Trial Fried Castle

The Lovely Wide Evil

The Bright Gene

The Infinity Half

The Lathe of Dr Dispossessed

To Murder Proud

The Sick Archbishop

Gun Man Blue

In the Silence

The Radio Who Dragons Through

Glory of the Dead

A Golden Geisha

The Sand Woods

Gates of Cholera

A Right Good Dawn

A Rosetta Ruby

New Tide Sky

The Fire Plan

Man to Barbarism

The Deception Needle

The Secret Electric Manifesto

City of Lost Faces

Jude the Key

Mystic Germs

The Roman Woods

Gold Sweet Death

The Brand Morgue

Sweet Dreams Piano

Loving Shanghai

End of Lolita Childhood

Cold Geisha

The Last Baby

Good Journey into the Light

The Door Song

Song for Want

The Bitter Lady

In Me, Not Get Proud

Mystic Sex

The Death of Walter

Stop Heaven’s Sun

One Mystic Cannibal

the Cannibal’s Candle

The Secret Red Sky

People of the Fire

Stardust Winter’s Love

Johnny Never Gonna Stop

Gone Thunder Rolling

The Metamorphosis Fish

Snowy Spots the Rainbow

The Tabloid Bums

the Deep and Unbearable

Call of Fire

The Cuckoo’s Jekyll

The Red Tenderness

The Raven’s School

The Memories of God

The Cave Dragon

Jim the Savage

Black Song

I Was Toys

The Snows Creek Came

The Secret Land

The Well

The Last Lies

Lords of the Knife

Inside Physics

The Galaxy of Gone

The Satanic Playlist

The Bloody 9

Freakonmics: A Hard Black Dance

A Road Death

The Feast Baby

Lucifer’s Rainbow

A Severed Cage

Of Summertime Glass

Lucky Break in the Night

the knife Man

Prison Rain

The Door to the Cosmos

Solitude in the Frost

The Clockwork Chamber

The Black Queen

Back to the Wind

The Blind Fields

Marathon of Fear

Sophie’s Dragons

The First New Madre Soldier

Seattle Siddhartha

The Glass Dawn

The Beloved Metropolis

The Glass Temple

Steel Woods

The House of Inception

The Tao of the Third

Lonesome Winter’s Man

Sugar Acid

The Piano Ashes

The Anarchist’s Game

The Furious Tenderness

The Red Hallows

Paradise Demons

Demons of Time

Cosmos, I Ride

The Machine King

The King’s Blue Grass

The End of Kashmir

The Secret Soldier

Love of Sunshine

The Night of the Rose

Tea House Cowgirls

Death of the Stars

In the Red Morning

The Star Queen’s Face

River Demons

The Night Runner

The World of Chocolate Songs

A Purloined Cloud

The Art of Hanging

Ode to the Sleepers

The Gold Inside

Even the Asphalt

Rogue Funeral

Sea of the Red God

Some of those are not bad! As a friend said, it swerves from the banal to the brilliant. There are some awesome ones, like:

- The Art of Hanging

- Lucifer’s Rainbow

- Sea of the Red God

- River Demons.

- The Invisible Deep

- Black Song

- The Memories of God

There is also some comedy gold like “China Hooker Tomatoes”!

You can also see it’s not a great idea to include portmanteauwords like “Freakonomics” as that is clearly someone else’s famous title, so whenever it shows up you’ll be breaking copyright if you decided to actually name a book that way. Better to use generic words. Although I quite like “Freakonomics: A Hard Black Dance”, it might make a good followup to the classic original by Steven D. Levitt.

I had even higher hopes for a sentence level RNN but unfortunately I wasn’t able to find a decent set of working code to test out when I was testing this a few months ago. I found several papers out of China that looked promising. Then, of course, in my hiatus, someone went ahead and did a kickass blog post on sentence level classification with code! I will likely do a followup after I test some of the new choices out there.

NLP and Beyond

That said, I am not sure that what these systems produce is really heads and tails above random word generators. It’s pretty good, but if you look hard enough you recognize it’s basically a semi-random mashup of already good titles.

If I’m being honest with you, I have to admit I don’t find these types of systems very effective for cranking out Shakespeare and titles, much less “unreasonably” effective. This kind of sentence level generator is mostly a parlor trick that obscures what NLP really does well.

It turns out that NLP is much better at more restricted problem sets, like sentiment classification.

In fact, you can get a good breakdown of the state of the art from a lecture from the Stanford NLP intro course. It’s just slightly out of date in that a few of those problems were solved better in the last few years but it’s still a great intro to the field.

So what’s the State of the Art? Here’s a breakdown from the video:

Mostly Solved Tasks:

- Spam detection

- Parts of speech tagging: (adj/noun/verb)

- Named entity recognition

Making good progress:

- Sentiment analysis

- Coreference resolution

- Word sense disambiguation

- Machine translation

Still really hard:

- Question answering

- Paraphasing

- Summarization

- Dialog

These systems shine when you go with what they’re good at doing, not against it, as I discovered with my title experiment.

What do all those tasks have in common?

In essence, these systems are good at predicting the next likely word in a previously understood sequence. They can also break down a sentence into its component parts or figure out if a sentence is positive or negative.

What good is that you wonder?

The answer is probably in your pocket. Or you’re staring at the answer if you’re reading this on your phone. I’m talking about the Google Assistant or Siri.

After training these systems on millions of hours of people talking, these AI assistants can take an audio sample and quickly disambiguate a garbled word by predicting that the most likely next word is “help” instead of “halter.” In fact, I’m finding the new Pixel phone, which is bundled with the latest Google Assistant to be smashingly good at this kind of task. It rarely predicts the wrong word when I talk to it.

Even better, it seems to understand a lot of semantic context to what I’m asking of it. For example when I say “Show me a bunch of good restaurants nearby” it knows to show highly rated restaurants near me rather than a random selection crappy rated eateries. That’s very, very cool.

It turns out that what I asked my fledgling AI NLP baby to do is a particularly hard problem that just isn’t solved yet. In hindsight, it’s not hard for me to figure out why as a writer.

While NLP practitioners are focused on decomposing a sentence into its most basic building blocks, a great writer knows that the power and meaning of writing comes from the words working together, not taken in isolation.

The real patterns I was hoping to detect are much, much different. They’re the stuff of art, such as poetic turns of phrase and unique word combinations. Let’s take a look at a few great titles to see what I mean.

The Sound and the Fury of China Hooker Tomatoes

Here’s a famous title from Maya Angelou. It’s one of my favorites:

1) I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

This is an incredibly advanced title construction that highlights why NLP is so challenging.

First of all, there are very subtle structural problems for machines here. For example, the title rolls off the tongue but there is no clear reason why. It’s not using any obvious literary techniques, like alliteration, that we can easily point out. If we can’t find it, the machine probably can’t either.

Now, it’s arguably using a technique called sibilance, which is either the reputation of S sounds or just speaking with a low level whispering type cadence, though it’s not using it precisely because there is only one S. Sibilance makes for a sensuous or sinister feeling. Think of a lover whispering in your ear or a snake hissing, both of them using the S to excite or terrorize you.

Actually if you’ve ever seen Angelou speak she uses a great deal of sibilance, so perhaps when I read it, I just hear her voice in my mind? And that brings me to the second major problem for machine interpreters:

An NLP system can only understand meaning from what is directly contained in the text itself.

Unfortunately, for ML gurus communication does not exist in a vacuum.

The real power in this title comes not from what is on the page but what feelingsand associations it creates in the reader’s mind.

We bring our own ideas, life experiences and feelings to everything we read. Without that context, a machine can’t figure out the higher order understandings that make this title incredible.

For example, a bird is born to fly. That is its primary purpose. Yet, the bird is restricted from what it’s designed to do. It’s stripped of its reason for living and so it sings in its desperation and fever. It sings because it wants to be free, to soar and see the world as bird is meant to and so sadness saturates this title. Of course, if you know the author’s history and the tragedies in her own life, then you can see why she chose it as the title of her autobiography.

This is something that simply can’t be teased out by using a clustering detection algorithm. It has comes from your associative understanding.

But all is not lost!

Let’s take a look at another great title and see if we can pick up more meaning from only what’s there in front of us.

2) Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

This title is easier for a basic algorithm to work through. It has several obvious poetic techniques, such as alliteration, which is a repetition of consonant sounds like “g.” Since this has actual alliteration, as opposed to only associated alliteration, the system should be able to pick this kind of pattern up.

It also has what I call the “union of opposites.” You tend to find this kind of dynamic juxtaposition in famous titles like “The Song of Ice and Fire”, or “Pretty Little Monsters”, or even historical events like “War of the Roses”. Flowers and destruction are not precise opposites but one could easily be considered to have a positive sentiment (roses) and the other negative (war). Some great titles are built on this principle alone, like War and Peace.

It also uses evocative and sentimental words like “midnight” and “garden”. These words create picturesque images in the reader’s mind, both frightening and beautiful. A system could easily be designed to understand these emotionally charged words, because marketers have been picking out “power words” for a hundred years.

When Doves Cry

Ambiguity is a very hard to deal with for NLP systems and yet it’s at the very heart of what makes for great writing, in particular fiction, literature, film and poetry!

It’s one thing to grasp the deep structure of how a basic sentence is constructed. If you were unlucky enough to live through sentence diagramming in grade school you learned how to slice up a sentence into its component parts. But while this might be interesting to teachers, editors and math peeps, you might be surprised to find that to a writer it’s plain old torture.

I hated sentence diagramming!

That’s because my fellow authors and I understand that the true power of words comes from somewhere else. It’s one thing to detect parts of speech. It’s completely different to detect what makes a phrase that sets a person’s heart on fire.

Sentence diagramming does not a writer make.

Even that sentence is not something a machine could comprehend. It’s basically bad grammar. And yet by using it, it forces you to stop and notice it. You have to pause for a split second to process it, even if that happens at an unconscious level. If I did that at a key moment in the plot of a great novel that I wanted you to pay close attention to, you might stand more of a chance of picking up on it as a reader.

And That’s That

OK, so maybe we didn’t get the next great title for book two of The Jasmine Wars. Eventually I created my own title, based on a line from a Chinese sci-fi story in translation called Invisible Planets, Through the Darkening Sky. I wanted to evoke the image of a storm that’s coming, that you can’t escape. You can only hold on and go through it. By the way, here’s the new cover below. I love the artwork, done by an amazing artist Ignatio Bazan Lazcano.

But don’t let my failed automagical title generator experiment hold you back from diving into NLP!

The field is currently enjoying billions of dollars in research and a true renaissance as it powers more and more essential apps like Google Translate, digital assistants and even real-time translation engines that live inside ear buds. It’s critical that we teach machines to understand us better.

If you want to learn more, then head on over to the Stanford course on NLP. Or just keep hammering through some of the blogs in this article. I won’t lie: It’s not an easy subject. As we saw, language and math are often at odds. They seem to exist in different parts of the brain, which is why people often do well on only one part of the SATs, either math or English.

And yet, there is a strange unity to language and math. They’re woven together in unexpected ways, like the 5–7–5 rule of Haiku. I can’t help but think that tomorrow’s systems might discover all kinds of hidden patterns as they work their way through the great art and literature of the past. Perhaps there’s a hidden pattern beneath the sea of words that goes so deep that even a writer can’t sense it, except in his dreams.

And maybe, just maybe, there’s an AI, waiting to be born, that will one day sing the songs that make the whole world sing.