HEATHER E MCGOWAN

“Most of us can remember who we were 10 years ago, but we find it hard to imagine who we’re going to be, and then we mistakenly think that because it’s hard to imagine, it’s not likely to happen.”

On September 10, 2001, no one would have imagined the events of the following morning, events that are now tragically etched in our minds.

Similarly, no one would have predicted last November or even December the seismic shifts in political and economic policy that are unfolding now. The Financial Times is advocating for some form of universal basic income in the United States. The US government is sending $1,200 checks to 80% of Americans. Gig workers are getting sick pay. Car insurance companies may send you a check due to sudden a decline in auto accidents. Some are even arguing that providing healthcare for everyone in certain circumstances may be in our collective best interest, that the federal minimum wage should be pushed up to $17.00 from the current $7.25.

It is already clear that, as I have written previously, that the coronavirus global pandemic is accelerating our adaptation to the future of work. And, it seems that coronavirus pandemic is also forming a social safety net that could reshape our future of work.

Most strikingly, this crisis is presenting the third existential challenge of the last fifty years. The first is climate change, the second income inequality, and the third is this global pandemic brought on by the latest novel coronavirus. Each of these challenges are reshaping work in some way, but it is this third test, one that is freezing our economy and forcing job losses for many and job changes for all, that will require our response to all three. We will either emerge in a post pandemic world with clear answers to climate change, income inequality, and global health or we will find ourselves with greater inequality and declining collective health.

My hope is the former, and to understand how we might emerge, it is helpful to understand how we arrived where we are and what this global pandemic may just change, for the better.

Income Inequality And The Employee

In 2014, I wrote a series called Jobs Are Over: The Future Is Income Generation in which I suggested we start thinking more entrepreneurially about our ability to learn, adapt, and generate resources rather than simply codifying and transferring existing knowledge and predetermined skills in order to create a deployable workforce. In part four of that series, I described how our current work structures, specifically the role of the employee with all requisite benefits, emerged from the Stabilization Act of 1942 in which President Roosevelt, in effort to stave off inflation, fixed salaries and wages leaving employers to offer other benefits like health insurance and retirement to attract top talent. This worked well for a few decades when most of us enjoyed those employee benefits.

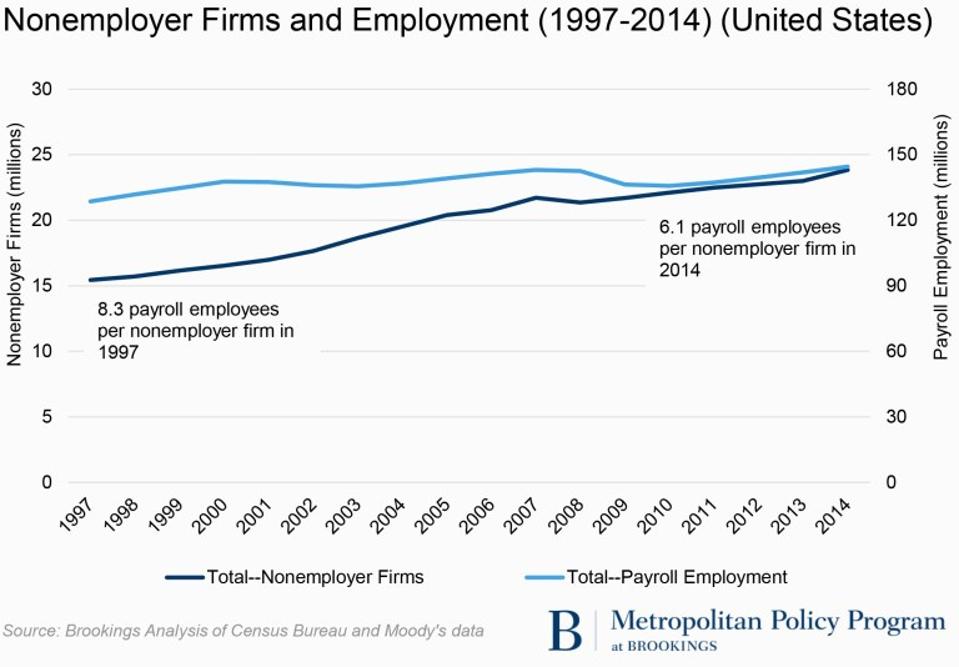

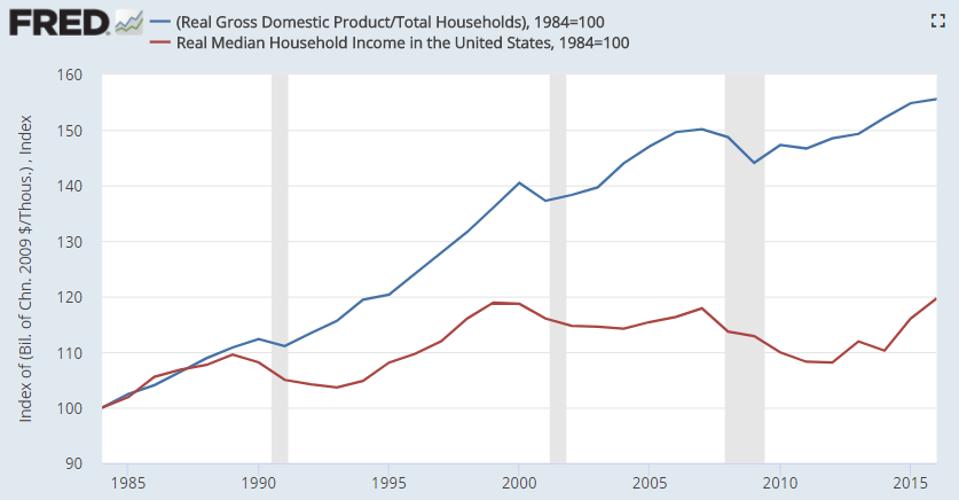

Then, Milton Friedman declared– that the only social responsibility of a business is to return profits to shareholders, a declaration that fueled the merger mania of the 1980s. This period also marked the great decoupling of GDP per worker from median household income, which simply means workers were increasingly productive yet did not share the gains proportionately. In the shadows of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, enabled by tectonic shifts in technological capabilities, we saw the rise of the gig economy. The Friedman doctrine and merger mania together stripped benefits from employees while higher productivity and the availability of the gig economy reduced corporate employment across the board. At the same time workers found less social mobility and higher education cost skyrocketed, placing a debt burden on a new generation of workers. Each of these moves was driven by the notion that human talent was a cost to contain rather than an asset to develop—in my view, one of worst human-made, unforced errors in history. We have prioritized hoarding assets made in the past over investing in spawning a new generation of taxpayers equipped to create new resources.

Nonemployer First and Employment 1997-2014 METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM AT BROOKINGS

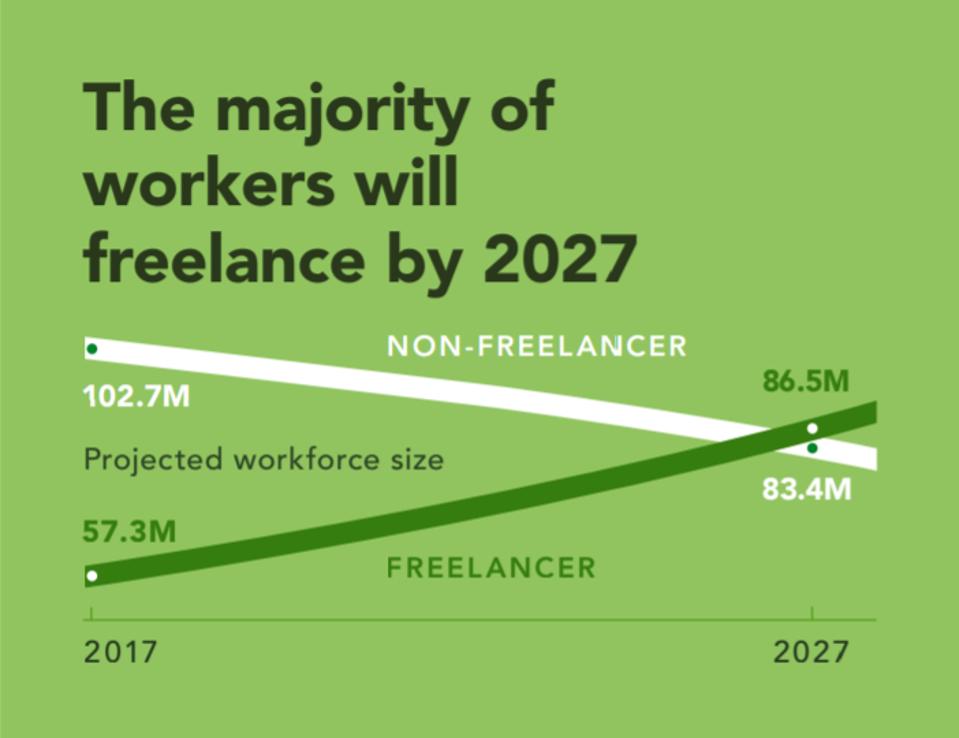

Freelancer’s Union and Upwork Believe The Majority of Workers Will Be Freelance in 7 years FREELANCER’S UNION

Image Source: Freelancing in America: Freelancer’s Union and Upwork

This has left us, today, with the highest levels of income inequality in the last fifty years. The United States is the most unequal of all developed nations. What does this mean and why should you care, especially if you are in the minority enjoying greater gains? Even if you are not motivated by your fellow Americans’ well-being, you might want to think more long term about your own, and perhaps more acutely, your children’s futures. Rising income inequality results in lower economic growth, research by the World Economic Forum found specifically that, “Overall, our empirical results provide support for the hypothesis that income inequality is beneficial to economic growth in poor countries, but that it is detrimental to economic growth in advanced economies.” That is where we are with income inequality in the United States pre-virus. Now the global pandemic shines a new spotlight on the liability for all of us in these inequities.

US GDP Per Capita vs. Real Median Income FRED

From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

Our Inequities Are Undeniable

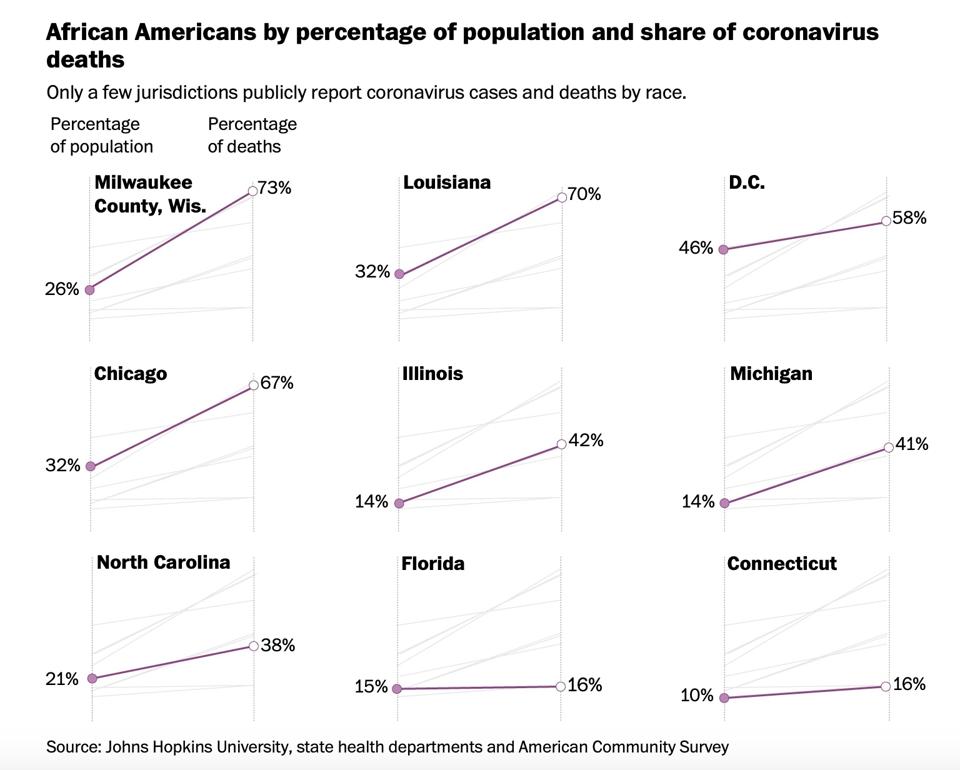

While we say we are in this pandemic together and that the virus does not distinguish between race, class, political party, or income, that is not entirely true. How we experience this quarantine varies greatly based upon income, and both infection rates and fatality are wildly different based upon race. These disparities are not based in genetics but rather in the inequities in access to our healthcare system (underlining health conditions), housing density (propensity to spread), and those who work on the front lines from grocery store workers to delivery folks to hospital workers (exposure). The virus could either exacerbate these inequities or we could see this as a moment, born of necessity, to re-knit our long-lost social safety net to enable more of us to contribute meaningfully to our society and economy and thereby release more of our collective human potential. As we begin discussions of lifting or lessoning quarantines to restart our economy will we reduce front line worker pay to pre-virus levels? Will we retract the two-week paid sick leave offered to minimize the spread of the coronavirus? Will we remove the access to and coverage for healthcare offered in this crisis?

African Americans by percentage of population and share of coronavirus deaths WASHINGTON POST. SOURCES: JOHN HOPKINS UNIVERSITY, STATE HEALTH DEPARTMENTS, AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY

Fifty Years of Climate Change Warnings

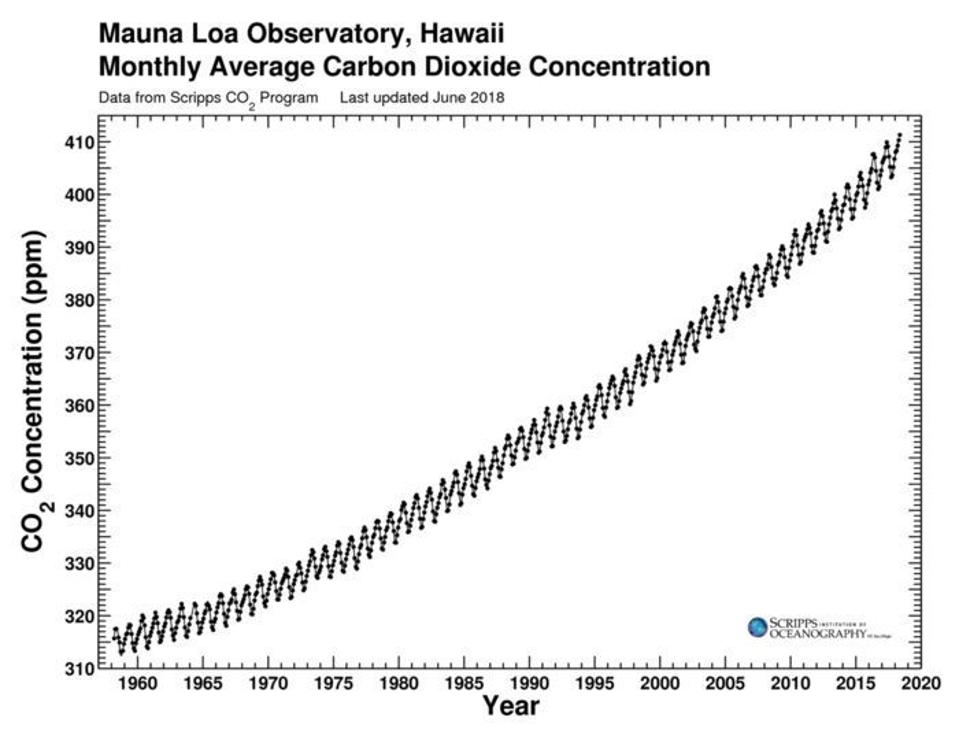

We have had ample warnings about climate change for more than fifty years. The Keeling Curve, measuring CO2 in the atmosphere, has skyrocketed since it was first developed in 1958. The first earth day was in 1970. In 1988, NASA Scientist Dr. James Hansen testified before the Senate that the planet was warming, and human behavior was the cause. In 2006, former Vice President Al Gore won an Academy Award for his climate crisis warning An Inconvenient Truth. And most recently, Greta Thunberg, catalyzed a global youth movement of activism for climate change that gave her audience at the United Nations and The World Economic Forum, and landed her a Nobel Peace Prize nomination and Time Magazine Person of the Year honors in 2020. All these warnings, all this attention, and we have not changed our behaviors. The five hottest years on record were the last five years and the ten hottest on record were in the last fifteen years. The World Bank Estimates we may have 143 million climate migrants by 2050 up from 22-24 million today. Per a recent article in the Guardian, “Insurers have warned that climate change could make coverage for ordinary people unaffordable after the world’s largest reinsurance firm blamed global warming for $24bn (£18bn) of losses in the Californian wildfires.”

Keeling Curve SCRIPPS OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTE

As we pause our economy, shutter our factories, restaurants, sporting events, and concerts, we both drive and fly less we are temporarily reducing our carbon output. Some of this will reverse when we restart the economy as we will inevitably reconnect and remap supply chains, resume our daily activities, but we may just take this pause as a moment to decide which activities to curb or change in favor of better climate stability.

Even if you are not facing the threat to losing a waterfront property or the likelihood of fleeing your homestead due to wildfire, superstorm, flood, or drought, if you are sitting at home, like most of us, reading this, you may take interest in the connection between climate change and the rise of zoonotic illnesses like the latest coronavirus.

2000-2020 Rise of the Zoonotic Viruses and The Global Pandemic Norm

An estimated sixty percent of infectious diseases are zoonotic, which means pathogens familiar to animals jump species to humans who have no natural immunity, creating an immediate public health crisis. In the last twenty years, Ebola, bird flu, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), the Rift Valley fever, sudden acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), West Nile virus, Zika virus disease, and now the coronavirus have made the jump from other animal to human species.

Why is there a rise in these zoonotic outbreaks? Will we see more frequent global pandemics in the future?

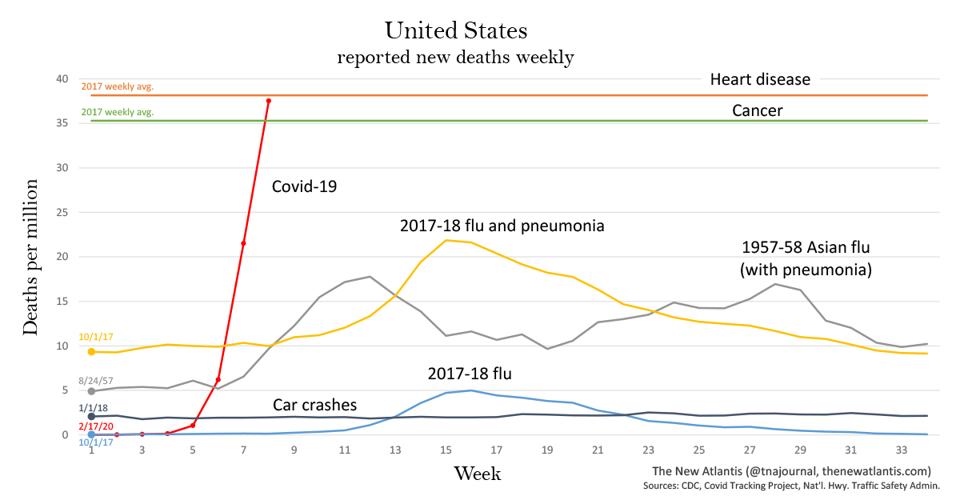

Coronavirus in Context of Other Causes of Death THE NEW ATLANTIS

The United Nations Environment Programs identifies potential liabilities for zoonosis outbreaks. These liabilities result from human and animal interactions driven by climate change, agricultural expansion, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. For example, human population spread and the subsequent need for more resources are encroaching on wildlife and driving more human-to wildlife and wildlife-to-livestock interactions have caused a sharp increase in zoonotic transmissions. In 2014, after the Ebola outbreak was contained with just over 10,000 lives lost, Bill Gates gave a TED Talk in which he warned we are not ready for the type pandemic outbreak we are currently experiencing. Watching it now is eerily prescient.

Pausing The Economy in Pandemic Is a Better Economic Bet

The coronavirus came to the US in the midst of a raging stock market and record unemployment. Yet, our response, ultimately, was to put our elderly, those with underlying health conditions, our healthcare workers, and our healthcare system itself before our economy. We made the right decision. We put people before profit, and in doing so, we are beginning to clearly see the inextricable link between the two. Freezing economies around the world is a very difficult decision because, even with massive government financial support, doing so puts very real hardship, and in some cases unrecoverable damage on our society. For example, when unemployment goes up so do rate of suicide and premature death. As hard as this is to face, this may have been not only the right decision to protect our most vulnerable and also our healthcare system, but also for our economy long term.

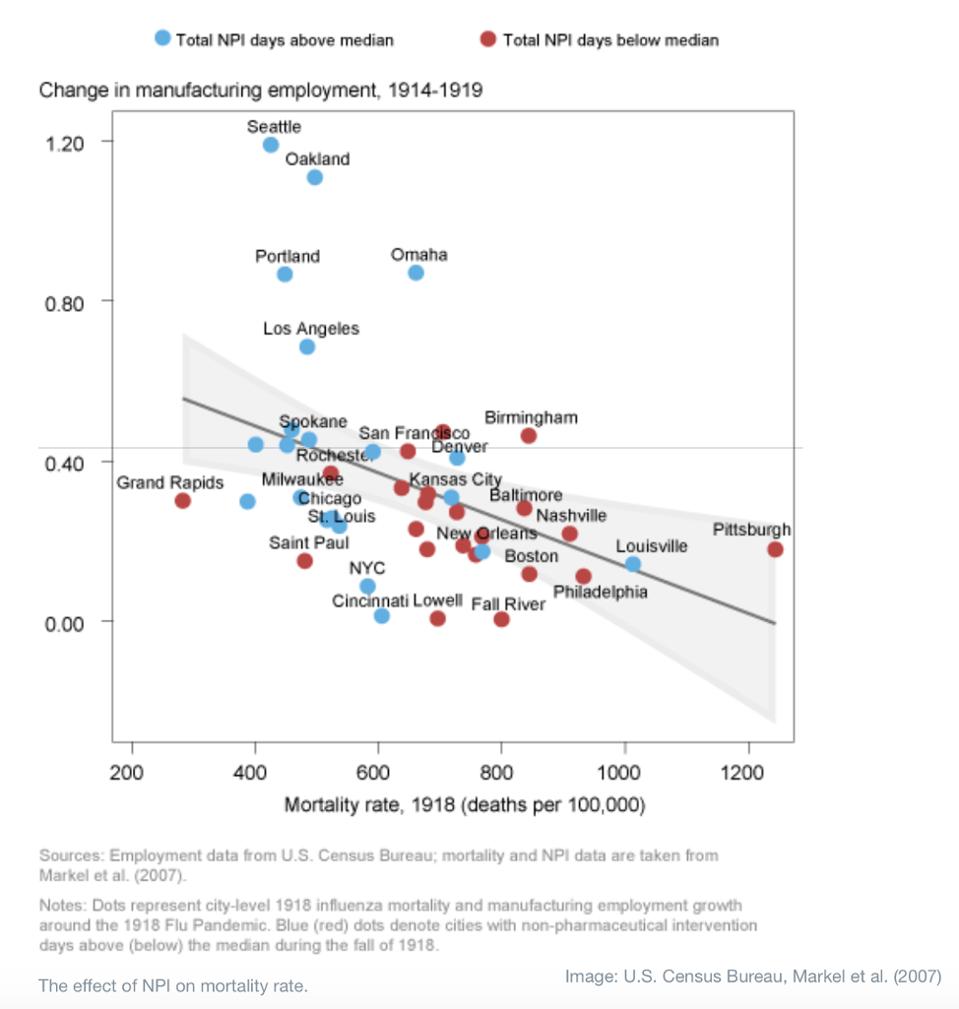

Fascinating research by the World Economic Forum examined the 1918 global flu pandemic and found that non pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) such the physical distancing limited spikes in infections and better protected our healthcare workers and healthcare system, ultimately avoiding even more massive casualties. This information is not surprising and it’s why we are all practicing physical distancing now. As importantly, the WEF research found, cities that enforced NPI early and aggressively saw no adverse economic effects over the medium term and an increase in real economic activity when the virus subsided. Notably, “cities that intervened earlier and more aggressively experienced a relative increase in manufacturing employment, manufacturing output, and bank assets in 1919, after the end of the pandemic.”

So, while we are feeling the near term, and for many tragic, economic pain, by prioritizing our health over the economy, we are also making potentially the best long-term economic decisions.

Effect of NPI on Mortality Rate US CENSUS BUREAU, MARKEL ET ALL

In The Pandemic Basic Income Moves To The Mainstream

In this pause, or as some, like Gary Bolles have suggested “The Great Reset”, we are discovering how quickly we can adapt and how some concepts previously considered unthinkable are now seemingly more inevitable. Universal Basic Income (UBI) was promoted only by fringe groups but as the virus lays bare the true gaping holes in our social safety net, it suddenly becomes in our collective best interest to address them. Some, prior to the pandemic, suggested that UBI could grow the economy, particularly in the near term by stimulating demand and creating more jobs. Others believed that Basic Income (BI) targeted at the most vulnerable (like the experiment in Ottawa Canada that was interrupted due to changes in political parties) could improve health outcomes and lower healthcare and social service costs. Now, we’re seeing greater support, even from more conservative thinkers, for some form of targeted basic income or critical basic income (CBI) is needed in the face of the pandemic. From Ken Boessenkool, partner in Kool Topp & Guy Public Affairs in Canada, to the Editorial Board of The Financial Times of London, to the country of Spain to United States Republican Senator Mitt Romney of Utah, a fringe idea promoted by presidential candidate Andrew Yang is now a mainstream reality. In a post-virus world, will we rip this support from our most vulnerable? Or is it in our collective best interest to raise the floor for folks so that more of us achieve our collective human potential?

We Are Interconnected, Your Health and Education Are in My Best Interest

If your Uber driver, Amazon delivery person, or grocery store clerk had health insurance or paid sick leave in November 2020, you might have seen their health as their problem. In April 2020, you may start seeing it as your problem if they work when sick, or cannot get tested or treatment, and then transmit the virus to you. We have long known that higher rates of education yield greater economic activity as well as better health outcomes and longevity, but we have not often enough considered the public return on investment in human capital. Our mindset and outlook has been me instead of we. We have seen the world as a zero sum game rather than an investment in collective return. For example, for our most at risk populations struggling with poverty, the return on investment in the most vulnerable populations is profound. For example, Rob Grunewald and Arthur Rolnick found in their Proposal for Achieving High Returns on Early Childhood Development, that every dollar invested in high quality early childhood development yielded between $3 and $9 in return and likely even much higher. As suddenly as we saw companies shift to work from home and educational institutions leap to online, we see our healthcare systems adapt to expand access via widespread adoption of telehealth and lump sum vs. fee-for-service models of physician pay. The latter model places incentive on office visits and sick care, where the former favors better health outcomes. Our healthcare system is adapting as is our perception of what is in our own best interest. Will all these advances retreat with the virus? Will we continue to feel a growing sense of interconnectedness? Can we finally see that a we approach is, ultimately, better for me?

Human left femur, Tell Fara, Palestine, 100 BCE-200 CE SCIENCE MUSEUM LONDON

Our Healed Femur Moment

Anthropologist Margaret Mead was asked what she considers the earliest known evidence of a civilization. Was it clay pots, hunting tools, religious artifacts or some other indication of human adaptation? Mead replied it was a healed human femur bone found on a 15,000-year-old archaeological site. “Mead points out that for a person to survive a broken femur the individual had to have been cared for long enough for that bone to heal,” Dr. Jeffrey Oak of Yale Divinity School notes. “Others must have provided shelter, protection, food and drink over an extended period of time for this kind of healing to be possible.”

This is our healed femur moment. We must rise to the existential challenges illuminated by this insidious virus.

A Challenge to Catalyze Addressing All Challenges

This crisis is our call to action. We are a highly adaptable species with an orientation towards innovation and entrepreneurship. Dr. Anthony Brandt, professor of composition and theory at Rice University and David Eagleman, neuroscientist and professor at Stanford – both champions of human potential — describe the human drive to create and improve the human condition in their 2017 book, Runaway Species:

“Above all else, the relentless drive of human beings makes us unique among living creatures. It’s built into our brain, into our biology, and it’s why you don’t see squirrels building elevators to their treetops or alligators inventing speedboats….Creativity lives in the predictability between exploring the unknown and exploiting what we know. We bend, break and blend everything we observe, and the fruit of that mental labor results in new and improved versions of the world.”

In this current moment, we see the “relentless drive” to innovate and collaborate at every corner of the globe and in every industry from pharmaceutical companies racing to find a vaccine, therapies, and treatments to companies rapidly pivoting their product lines to address the shortages of hand sanitizer, personal protective equipment, and ventilators. Companies are collaborating, from a Google and Apple venture to trace and track infection to a team of 100 people across Massachusetts Institute of Technology that rapidly came together to design a face shield that can be produced for a below industry cost ($3 each) and high scale (100, 000 units a day). We see national and international coalitions forming to fight the disease. Governors across the United States are coordinating respose and sharing ventilators after one state has flattened the curve to respond to another state’s need. To support its neighbor, Germany is taking on COVID patients from Italy. This pace of innovation and collaboration is working to defeat this virus and can meet this generational challenge.

If we can defeat this virus, we can also respond to its call to action: that we no longer ignore the inequities laid bare by this pandemic or lose the gains we have made in reducing our carbon emissions in during this pause. Today, the only thing growing faster than the virus is our collective sense of empathy, our ability to adapt, and our rapid and effective ability to collaborate. Our challenge now, even when the virus ebbs, is to continue to improve the human conditions and unleash the potential of everyone. That is truly in our collective best interest.

Thank you to Chris Shipley for always checking my blindspots and her invaluable contributions to this piece and to Retired Major General James Johnson, former Human Resilience Executive Director at the United States Air Force, for his review and meaningful insights.

This article was previously published on Forbes.